5 minutes

Stack Buffer Overflow

Revitilizing very old post from the past. Of course, my thinking has changed since then, but its always fun to open a time capsule.

What is stack buffer overflow?

Stack Buffer Overflow is a very neat security vulnerability. I was fortunate enough to learn and work on it during my security course at NC State. It can be defined as an anomaly where a program overwrites the buffer allocated to it and writes into adjacent memory.

How can this be beneficial?

Well, you can potentially overwrite a return address and make it point to some malicious code. When the system returns to that address it executes the malicious code allowing an adversary to take control of your system.

Why would anyone want to do this?

Money, research, fun, your kung fu master ordered, some celestial being commanded, I am not the one to judge.

How do you do it then?

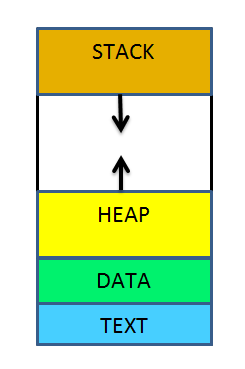

Well, to understand how to overflow a buffer you must know how the stack works and for that you must know where the stack is located. This is a typical diagram of the system memory layout.

Stack usually take higher addresses and grow downwards. Yes, the stack grows downwards. Would stack buffer overflow problem be solved if the stacks grow upwards? Hold on, I have not even explained how buffer overflow works. As a matter of fact the stack growing direction does not matter as we will find out soon.

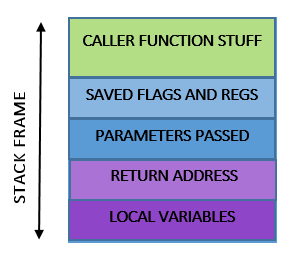

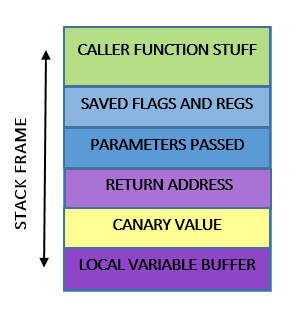

Every program that calls a function uses a stack. The contents of a stack are logically divided into a stack frame that belongs to a particular function that are monitored by two pointers ebp and esp. A function uses a stack to do the following

- To store the return address of the caller function.

- To pass any parameters to callee function.

- Callee uses it to store local variables.

- Any flags and state of the registers before the function call.

Check out this awesome site to know more on how stack works during a typical function call. In the above enumeration, No. 3 is the one that causes all the trouble. We shall see why. Here is the diagram of a typical stack with everything I have told you so far.

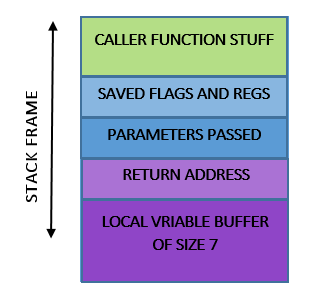

Now, consider a simple program like

void bar(char *str)

{

char c[7];

strcpy(c, str);

}

void foo()

{

bar(“wolf”);

}

The stack frame of the function bar will look something like this

what would happen if I sent, instead of ‘wolf’, a parameter of size greater than 7? strcpy is a function that simply keeps writing into a buffer without bothering about size. Any argument of size greater than 7 will overwrite the return address.

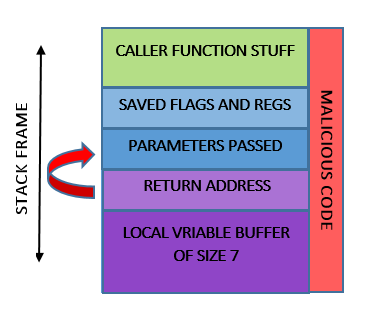

A potential attacker could send malicious code to the function and it will be happily overwritten onto the stack. So exactly how can an adversary use the stack to gain control of the system?

All he has to do is overwrite the return address and more data with malicious code. This is important, the return address should be pointing to the overwritten malicious code. Or, another hack you can do is point the return address to a bank deposit function and money will be deposited in your account again and again. Neat eh? Well, it’s not that simple. Here is how the stack should look after your attack.

Now, the return address points to the stack itself, which will be popped into the EIP register and potentially executing your malicious code. The malicious code is usually shellcode which is used to obtain a new shell to run your commands.

This is cool. But how do you counter such an attack?

Some basic best practices could be to always code using strncpy instead of strcpy which is not vulnerable to such an attack. But, there is tons of legacy code out there and strcpy is not the only vulnerable function. Other defences against such attack are

1. ASLR ( Address Space Layout Randomization)

Here the stack frames are allocated randomly so the return address that needs to be overwritten cannot be guessed easily. But we know that there are limited number of addresses in memory and programmatically we can try everything possible.

2. ExecShield and StackGuard

ExecShield marks certain address space as ‘stack space’ and does not allow any code execution in this address space thus making the above buffer overflow futile.

Stack guard is amazing, it modifies every stack frame to have a canary value like this

Canary value is a random value that is stored here and also somewhere else, which is verified every time a function returns. This gives very good protection against buffer overflow as it is very difficult to guess the canary value.

So, if we have these protections are we safe against buffer overflow?

Apparently not. Since other local variables can still be overwritten. What if one of the local variables is a function pointer? you can overwrite it to point to some malicious code and when that function was to be executed, it executes your code instead. It is possible to get such scenarios and CVEs (Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures) are full of them.

One final question. Does stack growing upwards solve this problem?

No, upwards stack does not solve our problem as explained here. It only shifts the problem, in an upwards stack the frame hijacked would not be the callee as shown above but could be the one whose stack frame is above the one currently called. Thus, most modern architectures continue to make stacks grow downwards.

References

- http://www.cis.syr.edu/~wedu/seed/Labs/Vulnerability/Buffer_Overflow/Buffer_Overflow.pdf

- http://www.csee.umbc.edu/~chang/cs313.s02/stack.shtml

- http://www.quora.com/Systems-Programming/Stacks-that-grow-up-are-a-solution-to-the-stack-buffer-overflow-problem-But-this-design-is-not-widely-adopted-Why

- http://www.phrack.com/issues.html?issue=56&id=5

- http://www.securitytube.net/video/231